|

These days it's acceptable to dig through the Internet at work, even when it’s busy. For me it’s a form of release, like a cigarette break—five minutes of every hour I let my brain soak in something totally irrelevant, like famous crime scene photos or an old episode of Phil Donahue. Just a quick hit is all I need, anything to satisfy the urge for mindlessness before diving back into my job, where I spend long chunks of time writing headlines for men’s jeans.

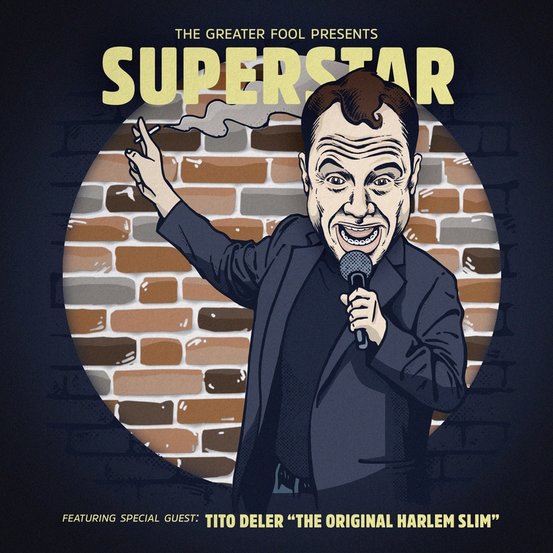

A couple years back, a creative director came into my office to check on a project. He lingered in the doorway, calling my name, but I was watching a YouTube video with my headphones on. Finally he tapped my shoulder. “What’re you watching?” he said. I paused the video and removed my headphones, and explained to him, rather meekly, that it was a Guns N’ Roses concert from 1991. He leaned in for a better look. The picture was fuzzy but clear enough: Axl Rose, frozen on my monitor, wearing nothing but skin-tight cycling shorts, a feather boa and a leather motorcycle cap. “Cool,” the creative director said, hiding his embarrassment for both of us. You’re allowed one of these, but when it happens regularly it becomes a running joke—the kind that starts with a chuckle and ends with concern. Whenever this person came into my office I’d be slumped at my desk, my head propped on my fist while I stared, glassy-eyed, at a different Guns N’ Roses concert. Rio de Janeiro, ‘93. Indiana, ‘92. The Ritz Ballroom, New York, 1988. Soon he came to expect it, and if I happened to be doing actual work when he walked in he’d ask, with sincerity, “Where’s Axl today?” Suddenly all of my downtime was devoted to old Guns N’ Roses concert footage. Some days I hammered out an entire two-and-a-half hour show before lunch, and then afterward I’d feel depressed, just wanting to go home and crawl into bed. I’d mope around the office in a crabby mood, unmotivated, barely making my deadlines, drinking a lot of coffee and eating bad food. It was as though I’d exposed myself to something radioactive that was slowly eating away at my physical and mental health. When I mentioned this to my therapist he said Axl Rose represented my own failed ambitions. “We’ve spent a great deal of time talking about your remorse over your career choices,” he told me, “and how you never put yourself out there or took any big chances.” He explained that Axl—who he’d only vaguely heard of before I introduced the subject—embodied the fearlessness and drive that, according to me, had been vitally absent my whole life. This, said the shrink, might explain the hollowness I felt after inundating myself with his concert footage. “Hitchhiking to L.A., living in squalor as a struggling artist, making music as a form of self-expression and getting paid for it…he took the ultimate risk, and he reaped the ultimate reward: he became a superstar.” Discussing a rock star obsession seemed appropriate inside my shrink’s soundproof office, but on the drive home, in the outside world, I felt like an idiot. I had just spent forty-five minutes talking to my therapist about Axl Rose—a ninety-dollar conversation, paid for by my health insurance. Now Guns N’ Roses was part of our repertoire, along with medically recognized issues like anxiety and depression. From that point on, whenever our meetings hit a lull, my shrink delicately broached the subject. “How’s the Axl Rose thing coming? Anything we should talk about there?” After five minutes of silence I open up. “I don’t know which is worse,” I tell him, “Not taking any risks, or not having the talent in the first place. I guess I’ll never know.” I’m referring to the summer of 2002, when I quit my job and drove out to Los Angeles to pursue standup comedy. It was a capricious idea that occurred to me while sitting on my drug dealer’s couch, high on painkillers, watching Jimmy Fallon host the MTV Movie Awards. “I need to go to L.A.,” I said, casually, the same way one remembers to buy life insurance after seeing an Allstate commercial. It was as though fame was on my to-do list and I just hadn’t gotten around to it yet. My mother felt the decision was impulsive and suggested a smaller first step. “Shouldn’t you try comedy in Boston at least once, see if you’re any good, before packing up your life and driving to the other side of the country?” A logical notion, but I wouldn’t hear it. When I make a go of something, I prefer to go all in or not at all. Like the time I took guitar lessons as a kid. My mother bought me a Hondo—a cheap electric guitar designed for beginners, basically a slab of fiberglass with strings. It was like learning to play tennis with a cinderblock, and after a year of plucking away at Beatles melodies, I quit. Had she bought me the $1400 Gibson Les Paul I’d asked for, who knows where I might be today. “I’ll spend the summer writing jokes,” I told her. “That way I’ll have a whole set ready when I leave.” I was living in my parents’ basement at the time, so my material varied between pathetic and creepy. “I tell ya, dating is hard,” I said into my microcassette recorder as I paced around the cellar, “dinner is usually someplace nice, like Applebee’s, and if everything goes well it’s back to my high school bleachers.” This was funny at first, but as I played back the tape a pitiful truth was revealed—this handheld electronic device telling me, in my own voice, that I was a loser. Joke after joke about living at home, watching sitcoms with my parents, discovering piles of clean laundry magically folded on my bed. I’d stop the tape and sit quietly with my thoughts, hearing only the faint sound of opera that chirped from my dad’s transistor radio, which had been sitting on his workbench and set to the same AM station since 1979. I have to leave here, I thought. And go far away. My plan was to travel light, to leave the past behind and start fresh. Somehow this meant a visit to the doctor before I left. Not my doctor, but Dr. Wang, who worked out of an urgent care clinic on the seedier side of Waltham. The waiting room was packed with cash-paying customers—a mix of quiet immigrants and frantic drug-seeking white people. “You said Tuesday!” a large pyramid of a woman yelled at the nurse, this while her three small children wrestled on the floor and threw Tinker Toys at each other. With her mullet and her oversized hockey jersey she looked more like a teenager from Winnipeg than a mother of three. “Call Medicaid. I’m sick of this crap,” she shouted with a voice that sounded like a dying robot. “I been waiting here two hours, and I ain’t going home without my script.” When the nurse called my name I got up slowly, clutching my back and wincing from imaginary pain. I walked in baby steps as she led me to the doctor’s office. “You back again?” said Dr. Wang. I wasn’t sure if he meant “back” as in return, or the part of my body with the phony injury. Both were true, as this was my third visit since June. I nodded, and then shivered as the neck movement pinched an imaginary nerve. Rather than ask how I managed to hurt my back again, his only concern was proof of insurance. Once that was verified he wrote me a prescription for twenty-eight Vicodin—enough to get me to Los Angeles, where I pledged to quit drugs and focus all of my attention on my comedy career. I thanked Dr. Wang and walked out of his office, elated, then remembered to hunch over in pain, at least until I reached the elevator. Wired from pills, I drove straight to Indianapolis on my first night. On the second night I made it to Denver. That’s where the drugs ran out. By the time I reached Utah, the following afternoon, a wave of depression hit me and I considered turning around and driving home. When I finally arrived in L.A. I was sick with withdrawal, shaking and dry-heaving in the parking lot of a Ralph’s supermarket. An hour later a Nissan Sentra pulled into the lot—my friend Jason, who was letting me crash with him until I got on my feet. He walked up to the car and knocked on my window. “You made it, kid!” he said, “Welcome to Hollywood!” But I stayed in the driver’s seat, staring straight ahead. Finally I rolled down the window. “I need to lie down,” I said, but it came out sounding more like “please kill me”. After four days on Jason’s floor I felt better and decided to find a job and my own place. The apartment came quick—a studio on North Sycamore, around the corner from Mann’s Chinese Theater—but the job search was fruitless. I started with the coolest bars and hotels in Hollywood and worked my down, all the way to a Kmart in Pasadena. I sat on my beanbag and stared at the application, the paper trembling in my hands, the ink smudged from my teardrops. As I listed my references the phone rang. It was the bellhop from The Beverly Hills Hotel, who’d just come across my resume and offered me a job as a valet attendant. “Yes sir, thank you!” I beamed, throwing away the Kmart application. I’ve heard miraculous Hollywood stories like this before, someone about to throw in the towel when suddenly an opportunity comes out of nowhere and changes everything. This happened to Dustin Hoffman, who was on his way to the unemployment office when his agent phoned with a job offer. Of course, his was the lead role in The Graduate, and mine was parking cars for nine bucks an hour, but the symmetry wasn’t lost on me, and I took it as a good omen. I saw a lot of celebrities at the Beverly Hills Hotel, though they refused to see me. Every time I handed them a ticket or opened a car door they would deliberately turn away, the way one does when having blood drawn. Seinfeld, Tim Allen, Stallone, Rod Stewart—all dismissed me as a lowly servant. Only two stars were decent enough to smile and make eye contact: Dana Carvey and Jon Bon Jovi. I told myself when I hit it big I’d repay them by casting them both in a buddy cop movie. Though often demoralizing, parking cars at an iconic Beverly Hills institution fit with my image as an aspiring entertainer. I pictured myself in future interviews, listing off the odd jobs I did to support myself, looking back with fondness on their simplicity, before life was consumed by the daily assault of lawyers and press junkets. “Enjoy these moments while you can,” I told myself one night as I jogged through the garage, searching for Tony Danza’s Jaguar. Four shifts a week netted me about $240—a decent start but hardly enough to live on. The flexibility allowed me time to hone my comedy act and explore the club scene. First was the famous Laugh Factory on Sunset. I stopped by on a Sunday and bought a ten-dollar ticket to that evening’s show: Joe Rogan, who I knew as the host of TV’s Fear Factor. There were a half dozen people in the seats for the opening comic, and only a few more when Rogan took the stage. His act was loud and obnoxious, most of the jokes involving semen. The crowd was uncomfortable. It felt more like a behavioral study than a comedy show: the handful of audience members like scientists, sitting on the other side of a one-way mirror, sadly observing a disturbed man spiral into madness. The following day I returned to the Laugh Factory to sign up for its open mike night. Names were taken on a first-come basis, so for three hours myself and ten other amateur comics waited outside the box office, on the sidewalk, in plain view of the traffic on Sunset Boulevard. Whenever a fancy car pulled up to the stoplight everyone assumed a posture. One guy would start shuffling blank notebook pages to make it seem like he had an endless supply of jokes. It was humiliating, us standing there. I felt like an orphan with an empty bowl in my hand and a sign that read PICK ME. That night I sat in the back of the club, waiting for the host to call my name. After seven comics I took the stage, frightened as I stared out at the mangy audience. “So…I just moved to L.A.,” I began. “I like it here. There are apartments for rent. Where I come from we don’t have apartments, only parents’ basements.” I heard a few laughs, and my nerves calmed down. “I got a place in Hollywood. It’s called a studio apartment. It’s nice but I think it was false advertising because it’s nowhere near Warner Bros., Paramount or Universal.” A few more chuckles. “Has anyone heard of Steven Spielberg? I’d like to meet him. It’s on my list, right after opening a bank account and buying dish soap.” I closed out my five-minute set with a thank you to the millions of losers in Los Angeles who made me feel at home, especially those in my apartment building. “Thank you creepy guy in 3G,” I said. “I don’t know your name, but because of you I no longer feel ashamed when I get naked and stare out the window.” I waved to the crowd. “I’m Danny Pellegrini. Thank you very much. Good night.” The crowd applauded, a few even cheered. I stepped off the stage feeling like a true entertainer. Pay attention, I thought. They’ll be asking about this night for the rest of my career. My second gig was the following Monday at a UCLA bar in Westwood. I hadn’t written any new material, which was fine because I wanted to focus on my mannerisms and timing and not worry about remembering jokes. My confidence was high, fresh off the success of my first show. I opened with the same bit: “Out here you have apartments. Back home all we have are parents’ basements.” I was sure it would kill but the audience was silent. Not even a courtesy laugh. They stared back at me as though still waiting for the punch line. I moved quickly into my next joke about driving around my old high school smoking weed and listening to Van Halen. That one landed with a thud, too. “Okay,” I said, sweating under the hot lights. I looked up and saw a table of four college kids, talking amongst themselves, not even paying attention. I trudged on. “This summer I took a date to, uh, Applebee’s, and uh…” Now there was something in my eye, a flickering redness. I thought I might be having a stroke when I looked down and saw a red dot on my chest: a laser pointer—the modern day version of the hook. The emcee sat in the back of the audience, shining it on me. “Should I go?” I said. “Please,” he said into his microphone. I waved, dropped my head and walked off to the sound of a single sympathy clap. I’ve never been the resilient type. Sure, I’ve dealt with a full caseload of personal demons and health challenges, but with non-life-or-death stuff I tend to get frustrated or lose interest as soon as the waters get rough. Anything hard is stupid: learning to ice skate, writing a novel, maintaining a relationship. Even my own conversations fail to retain my attention. “Forget it, it’s stupid,” I’ll say halfway through a story about a police raid at my neighbor’s house. This frustrates my audience, and they demand I finish. I apologize and tell them I lost my train of thought, and then I blame them, saying they didn’t seem too interested anyway. In spite of my defeatist nature I vowed to pick myself up and carry on. Perseverance is what separates the successful from the rest of the crowd, I told myself as I repeatedly dialed my weed dealer’s phone number. Talent and skill get you in the game, but toughness keeps you there. I bought a book called Zen and the Art of Standup Comedy. I studied videotapes of great comedians. I hunkered down at a coffee shop on Hollywood Boulevard, writing ideas into a notebook. Often I saw costumed characters sitting together, the ones that pose with tourists in front of the Chinese Theater. Batman, Marilyn Munroe, James Dean, Chewbacca—all taking the same lunch break. At first it was delightful, but the more I listened to them the bleaker it got. Talk of eviction notices, verbal abuse from pedestrians, loved ones who cut them out of their lives. The reality that my make-believe heroes had terrible lives and survived off wrinkled dollar bills was too much for me. The final straw came when Superman stood up, threw a handful of coins on the table and called Freddy Krueger an ungrateful asshole. He stormed out of the café, holding back tears. From then on I went to Starbucks. After paying my second month’s rent I was broke. I had cigarettes and weed, but had to forgo certain luxuries, like hard drugs, and food. Then another miracle happened. A restaurant I applied to when I first got to town had passed my resume on to a club promoter, someone by the name of Johnny Eyelash. He wanted to meet me regarding a bartending job at an after-hours club on Melrose. In his voicemail he described the clientele as “exclusive, VIP-type” and said that he needed a “star bartender, someone worthy of an A-list crowd”. A-list crowd? Star bartender? That evening I met with Johnny Eyelash at the club’s location. I expected someone androgynous, like David Bowie or Andy Warhol, possibly wearing mascara and a velveteen jacket. To my surprise Johnny Eyelash was a pudgy 25 year-old Italian kid from Staten Island. He and some friends had moved to L.A. a year ago, opened a couple restaurants and were “diversifying”, as he put it. My shifts were Friday and Saturday, from two to six in the morning. “You’ll be making between five hundy to a G each night. All you gotta do is pour the drinks and look good. We need a star, kid. You got what it takes?” I told him yes, absolutely. Up to two thousand dollars a week for eight hours of work? My entire week would be free to pursue comedy. This was another omen, telling me to hang in there. The club was really just a recurring party held in a fourth floor apartment that, according to Johnny Eyelash, was once owned by Liberace. A fifty-dollar cover charge got you in the door, and after that drinks were free. I was told this system would work to my advantage, that an open bar meant customers would tip well, when in fact the opposite was true: people drank more and saved their remaining cash for the club’s cocaine dealer, who strolled around the dance floor looking somber and inconspicuous. The only celebrity I saw was Jason Priestly. He was huge when I was in high school, but his star had dimmed considerably, which might explain why he was at the club, and why he asked to borrow forty bucks. Still, the house was packed on opening night. I poured at least five hundred drinks. At the end of my shift, after tipping the bar back, I made $120. The next night thirty people showed up at the club. I stood behind the bar like a stooge, wiping tears from my eyes, struggling to stay awake. At three AM I bought a gram of cocaine from the club’s dealer. By six it was gone. I netted twelve bucks that night, minus the fifty I spent on drugs. On the drive home I blew a stop sign and crashed into a Buick LeSabre, a father and daughter on their way to church. Their damages were minor and luckily neither of them hurt, but my Acura was totaled. I managed to drive it back to my apartment without passing any cops, who surely would have been suspicious of a man in leather pants driving a car with a crushed hood early on Sunday morning. Club Liberace never returned to the glory of its opening night, and I never made more than eighty bucks a shift. I quit after a few weeks but maintained a good relationship with the drug dealer, who also sold painkillers. Whenever I saw him, life was good: he’d drop off a package in the morning and I’d spend the day walking through Hollywood, dreaming of a successful show business career. Days when I didn’t see him I stayed in bed and longed for the basics, like an appetite or a functioning car. My lowest points came at the valet job. During those days comedy was the furthest thing from my mind, and believe me, if I ever needed a sense of humor it was then, riding the bus down Sunset Boulevard, dopesick, dressed in my white sneakers, white pants and pink Beverly Hills Hotel polo. As we passed through the Strip I’d look out and see the Monday open mike amateurs, lined up outside the Laugh Factory, hopeful, wondering if the Gods of Fame will choose them. Better toughen up kids, I thought. This town will eat you alive. I don’t remember the exact moment I decided to go back to Boston, but for the story’s sake let’s say it was December 25th. I worked at the hotel that night, since the other valets had families, and I had nothing. It was slow and there wasn’t much to do but stand there at attention, my arms held behind my back. After a long stretch of quiet a car pulled up. I opened the door and greeted a young man, Carson Daly, who at the time hosted the MTV show Total Request Live. He thanked me, grabbed an overnight bag and walked into the hotel, alone. He seemed preoccupied and a little disgruntled. I wondered what brought him here on Christmas night. Then I wondered how he got started in show business. Then, for the first time in months, my mind became calm. The needling envy and discontentment were gone, and, at least for the moment, I felt okay about being a nobody. Eventually I got the insurance check for my totaled Acura. I bought a used Jeep from one of the valet guys and had enough left over for the drive home. I left everything behind: beanbag, dish rack, milk crates—all of it. Before heading out I saw a Russian doctor on La Cienaga. I told her my back hurt and she wrote me a script for twenty-eight Vicodin. Enough to get me back to Boston, where I’d clean up and focus on a new chapter in my life, something yet to be written. Or something that may never be written at all.

2 Comments

(From a journal entry dated May 7 2016)

The rule in movie theaters is: when the lights go down, it’s time to stop talking and bring your attention to the screen. There’s also an unwritten rule that works in tandem with that: while waiting for the film to begin, hushed voices are preferred. This is observed in most dimly lit spaces, such as fine-dining restaurants, say, or funeral parlors. The amount of light directly correlates with speaking volume. When I’m inside Target, which is lit like an operating room, I have no problem cupping my hand around my mouth and shouting to my wife, three aisles over, to remember the Preparation H. But in low light I have a natural tendency to whisper, giving the most trivial subjects—like basement dehumidifiers, or zero-percent APR financing—a clandestine and revelatory aura. Some people are unaware of this rule, or they choose to ignore it. These are the ones in the museum, screeching so loud that even the oil paintings cringe, or the guy who steps into the elevator, phone to his ear, making plans with someone named “bro” and assuring him that everything is “all good” while five strangers are sardined around him, fantasizing about his gruesome death. Maybe it’s the power trip that comes with hijacking a readymade audience, but I’ve never understood loud talkers. Call it paranoia or delusion, but I don’t want any unintended recipients hearing my conversation. Partly it’s out of respect for those within earshot, but mostly it’s because I’m weirdly protective of my thoughts. Do I really want the table next to me to know that I’ve invented a new laugh, one that’s modeled after the theme from Entertainment Tonight? Or my stance on tax reform, which I memorized from a Facebook post I read earlier that morning? If you’re going to command a space with your conversation, at least make an effort to use compelling material. On a recent flight to Palm Beach, two weight-lifting buddies in the row behind me discussed the properties of whey protein, an exchange that lasted from takeoff to somewhere over the Carolinas. They projected their voices and spoke with the kind of enthusiasm found in infomercials. Were they deliberately trying to drown out the jet engines? Were they showing off their commitment to physical fitness, or their knowledge of the local GNC? No one could possibly find this interesting, not even them. Now, revise the conversation slightly, change protein drinks to illegal steroids and make the health food store a warehouse in Chinatown, and you’ve got something. Take it a step further and change bench-pressing to organ harvesting, and I’ll gladly stow away my novel, sit back, and follow along. As it happens, the ones with the most interesting stories rarely speak loud. Sometimes you’ll overhear a gem, like “Susan, at some point we have to return that child”, but for the most part it’s just pointless noise dialed up to a higher volume. In movie theaters, the chatter leans toward film analysis, a topic that makes any moderately educated person sound like an asshole. Place any two people in front of an empty screen and they assume the roles of Siskel and Ebert. As such, they tend to dress up their conversations with scholarly language, using terms like “self-aware” and referring to movies as “exercises”. I find myself cheering on those who tell it straight, like the woman in front of me who ended a discussion on Argo by spitting out a fingernail and calling Ben Affleck a douche, or the teenager who summed up Zootopia by saying, “I don’t care if it won an Oscar, I’m not fucking seven anymore.” Last night Amanda and I saw the film Sing Street at a small, independent theater in the suburbs. Sitting behind us were a man and woman. I didn’t notice them when I sat down, but once I settled in their voices rose above the din and I was treated to my own personal radio show. Tonight’s episode was called: Who’s that actress? “…The one from that film, about the train, in India, oh she’s good,” said the woman. “You mean the one with Redford and Streep?” “No. It’s not a train. It’s a hotel. Why was I thinking train?” “Oh, you mean that woman from Misery, what’s her name, Karen Bates.” “Is that her? The one who played the Queen?” “The one who played the Queen…with the red hair?” Normally I would have simmered with rage, hating these people twofold: first for not remembering the actress’s name, and then for being so vocal about it. But as it were, I liked this couple. I couldn’t see their faces, but given the clumsy amble of their dialogue, I placed them somewhere in their late-sixties. Had they been younger than me I would have turned around and threatened them with violence, but it’s kind of sweet when older folk bobble a piece of pop culture knowledge. I could have turned around and politely said “Dame Judi Dench”, bringing an end to the mystery, but, as an audience member, I enjoy being one step ahead of the characters I’m following. It’s a common narrative technique that draws us into a story and heightens suspense. The ticking bomb in the suitcase. The woman who hides her terminal illness from her lover. The name of an Oscar-winning actress that escapes two people sitting in a movie theater. Eventually they moved onto another topic, and I got up and went to the concession stand. On my way back I got a visual of the man: narrow face, round eyeglasses, gray hair pulled into a ponytail, horseshoe mustache. The woman, sitting on the other side of him, was obscured. I sat down and handed Amanda a Diet Coke. She showed me her phone. On the screen was a picture from some realtor website. Amanda said something about an open house on Sunday, but that was drowned out by the loud, creaking voice of the woman behind me. “Did you grow up around Boston?” the woman said. I had originally pegged these two as a married couple, empty nesters probably. But given this type of get-to-know-you banter, it seemed more like a first date. Were they widowers? Divorcees? Or a pair of lonely hearts who, after a lifetime of searching, had finally found each other? “Boone, Iowa,” the man replied. “It’s a little town about fifty miles north of Des Moines.” The woman said “ah”. How else does one respond to Boone, Iowa? I turned my head slightly, trying to get a visual of the woman, when Amanda held out her phone again, this time showing me a picture of a different house. “Needham,” she whispered. “Fifteen hundred square feet, but only one bathroom.” I looked down at her screen, but instead of a ranch-style home I saw a water tower, looming before a Midwestern sky, the name BOONE stenciled across it. “My sister Gail married a man from Kansas City,” the woman said. “He owned a small manufacturing company that made medical devices, before he retired. His son Wade runs it now, so that’s nice.” There was a pause. I felt like more was coming. Amanda said something about emailing a realtor, but my attention was on Wade. Then the woman continued. “And what did you do for work?” Amanda asked if I’d heard back from my sister about Memorial Day. I shushed her. “I was a high school history teacher for thirty-one years. Now I work in retail, where I make minimum wage.” It was a bombshell of a plot twist. The history teacher bit, yes—that worked. But why retail? Wouldn’t he be tenured, and collecting a pension? To that end, wouldn’t he still be teaching? And if not, was he fired? And then the way he tacked on “where I make minimum wage”…so matter of fact, as though it was part of his job title. Not a trace of bitterness or shame. Why not just tell her he was a retired history teacher and leave it at that? It wasn’t a lie, just like the time I told a date I lived in Newton, but selectively left out the part about it being my parents’ house. There had to be more to this story. Just then I noticed a piece of popcorn in my hand. I’d been clutching it for the last five minutes and had compressed it into a small bit of yellow Styrofoam, matted with skin oil and liquid butter. I dropped it on the floor and wiped my hand on my pant leg. “Which retail store?” the woman said. “Petco. The one on Waverly Street. I work four nights a week. It’s okay, but my manager, she’s, well, she can be a little, I don’t know. I guess she’s just doing her job.” I imagined this man, with a gray ponytail, dressed in a blue polo shirt with the Petco logo stitched on the breast, standing behind the register, his finger hovering over one of the buttons. His eyeglasses are on the tip of his nose. He is lost, frightened. Next to him an impatient young woman holds a massive set of keys. My jaw hung open. My chest heaved with each breath. Ask him why he left teaching, I thought. I had to know. I felt Amanda’s hand on my leg. She shook her head and mouthed, “Stop listening to them. It’s rude.” Rude? I was sitting in my chair, staring straight ahead. Their conversation was loud and inescapable. The only way I could appear uninterested was to read something on my phone, or talk to Amanda about real estate. Why should I be forced into one of these alternate options, just to give these people a sense of privacy? “I became a teacher to get out of Vietnam. It was either that or move to Canada.” Now Amanda froze. Her head stayed straight but her pupils swung in my direction. Another wrenching plot twist, this one challenging my allegiance to the main character. Though he certainly wasn’t the only young man who’d objected to the war, fleeing from combat isn’t the most noble of things. On the other hand, divulging this to someone you hardly knew—much less on a date—was courageous. These are the ambiguities that make great characters. Do I like him or not? The answer lies somewhere between the two, in that complicated and murky space, prompting fierce discussions among audience members as they filter out of the theater. There was a pause, and the woman said: “My older brother was killed in Vietnam.” The lights went down, and the theater’s logo animated in bright colors on the screen, accompanied by its deafening jingle. This was followed by the Coming Attractions—a handful of trailers, indie films, all with the same basic plotline: four quirky thirty-somethings and how they navigate the obstacles of love, friendship and adulthood. The story I really wanted to see, though, was sitting behind me. |

AuthorDaniel Pellegrini is a recovering drug addict with an aggressive form of chronic bowel disease. That means he can't take painkillers after undergoing rectal surgery. He's here to show you just how beautiful life is. Best of the Fool:

June 2018

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed